You were born in New York. What is the process that led you to work in South America and to become an activist architect?

There are professional, philosophical, artistic and esthetic reasons. I was born in New York because my father was escaping dictatorship. Therefore I grew up in an idyllic American society and I lived a little bit the life of Manhattan and of the suburbs of Long Island.

MY FAMILY WAS VERY MUCH CLOSELY INVOLVED IN THE MAKING OF VENEZUELA AS A COUNTRY IN THE MODERN ERA. SO, SINCE MY YOUTH, I WAS CONSCIOUS OF THE DIFFICULTIES OF MAKING A NATION OR, IF YOU PREFER TO CALL IN THIS WAY, OF CREATING A DEMOCRACY OR EVEN BUILDING UP A CITY

At seven I came back to Venezuela and encountered the magic of mango trees, parrots, tropics, warm weather, sunny days; it changed my whole concept of the world and it completely touched me. Then I went back to the United States to college and architecture school at Columbia University, where I tried to combine being from both North and South America. Being a perfect example of both worlds, the North and the South, in Urban – Think Tank we naturally try to merge the intelligence of technology from the North with the kind of intelligence of ingenuity of the architecture from the South.

Why did you become an activist architect?

As I graduated from Columbia University in 1986, all I wanted to do was to return to South America. When I moved back to Venezuela I got a second degree at Universidad Central, in order to tropicalize myself. Whether in Columbia University I was taught how to make forms and parametric facades, in Venezuela I have learnt the principles of what I practice today. But at that time, Venezuela was going through a socialist revolution. So, after graduating, the question was how to develop a practice of architecture in an incredibly, increasingly volatile and changing country.

When I began to be interested in architecture it was for aesthetic reasons and not for the reasons of content, but then I realized that in countries with a significant ongoing process of change, it is all about content and about what your building can do and how it can empower people.

What does it mean to be an activist architect? Activism in architecture implies a shift of perspective in considering architecture as a mission way more important than just designing buildings. How does it feel taking this responsibility?

Manfredo Tafuri in his book ‘Architecture and Utopia’ or Aldo Rossi in his book ‘Architecture of the City’ say that architecture must take more responsibility. The great architecture of the modern movement is intimately related to the social dynamics of the city. In fact the best architects have been always coupled with a revolutionary change in society.

Le Corbusier, with his dictum ‘Architecture or Revolution’ for instance, said that either we build architecture for the masses or we will get revolution.

IN COUNTRIES WITH A SIGNIFICANT ONGOING PROCESS OF CHANGE, IT IS ALL ABOUT CONTENT AND ABOUT WHAT YOUR BUILDING CAN DO AND HOW IT CAN EMPOWER PEOPLE

In fact in my country we have not lost this spirit of modernism. Every student of architecture is trained also in the poor parts of the city, so there is a real concern about the social responsibility of architecture, or – to quote Giancarlo De Carlo’s – to consider architecture as a catalyst.

You worked a lot with the periphery. The periphery is associated often with marginality in terms of space (being at the edge). Of course there is way more than that. So what is periphery for you?

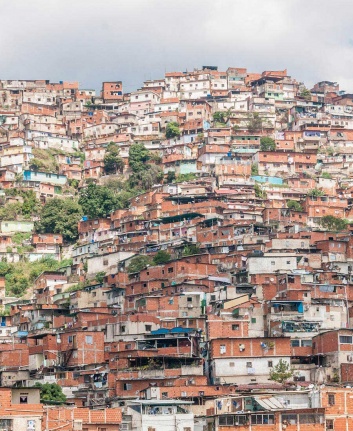

The point is that there is no center anymore. We are always in the periphery, you don’t know if you are inside the boundaries or if you are outside the boundaries. It’s all become a big blur. Rio De Janeiro and São Paulo, for instance, have favelas all spread inside the center like pockets. Mexico City, on the other hand, has all the poor population living in the core of the city. Caracas instead has all the poor people living on the edges and on the outskirts of periphery.

The center of the city is over-regulated, over-structured and over-formalized, so it is very difficult to reinvent architecture from the center. The periphery is therefore a laboratory that is looking to engage a more free type of development that can bring back renewed ideas to the center.Traditionally, architecture tends to consider the center as the focus of the discourse and the buildings as the center of the profession. Yet to renew the discourse, we, as Urban – Think Tank, went to the periphery: we went to the edges of our profession by engaging other disciplines. In fact the peripheries of the cities are the most interesting, the most amorphic, the more difficult and the more organic places. So the periphery is just a state of mind, it is not necessarily always a geographic position.

So, as I understand, there is always this kind of duality between the center and the periphery with the slums; between the formal city and the informal city. But how would you define the formal city and what is informal city? How can they integrate?

It is very important to note that what you call slums is what people actually call ‘home’. Actually, the term ‘barrio’ in Spanish means neighborhood.

So these informal cities are neighborhoods in formation: they have been formed over time. Informal is not the opposite of formal: the opposite of formal would be non-formal.

These barrios-neighborhoods have been formed just like the medieval city: organically, by approximation, built by people themselves. And this is why you like the old towns of Europe: the way the elements of the medieval cities are put together is actually the right reflection of a negotiation done with people and by people.

On the other hand, the modern cities are the cities of rationalization of the grid, of the commercialization, of control. They are not built by the people and for the people: they’re built by the 1% of the citizens for the 1% of the citizens. Architects have been complicit, they have been part of this process of creating islands of wealth and ghettos of poverty.

So the city corresponds neither to urban nor human complexity.

Correct. What we are doing at Urban – Think Tank is trying to create new tools. We go into the informal areas and we try to formalize them: we put new roads, infrastructure, transportation et cetera.

ARCHITECTS HAVE BEEN PART OF THIS PROCESS OF CREATING ISLANDS OF WEALTH AND GHETTOS OF POVERTY

I use the case-study of the ’23 de Enero’: the largest housing block project done in all of Latin America, built in Caracas by the famous modern architect Carlos Raul Villanueva. At the time it was built, there were no shops, no laundry, no services, no restaurants. It was basically a dormitory city. Over the time, from 1958, all the open spaces between the blocks of ’23 de Enero’ have been invaded by squatters and have been filled with a village of favelas, or, to be more accurate, barrios. This way in between the blocks grew a plug-in city (like Archigram) of favelas, plugged into all this open space and creating the shops, the restaurants, the laundromats. I believe that we need to bring the urban village to the modern city and then we need to bring the modern infrastructure to the informal city: we need to informalize the formal and formalize the informal. This way we can have a more even distribution of urban qualities.

So the process is going back and forth between the formal and the informal. But how does the human component fit into this process? I mean, the places where you work are literally shaped by people, not only in terms of space but also in terms of social dynamics. I guess that this requires some sort of sensitivity that goes beyond the architectural practice as it is normally conceived.

This is a very important question. None of the ideas that we work on are invented by us. We develop our ideas with a team of non-architects: sociologists, writers, filmmakers. We do not do any construction without at least a good amount of research that involves dialoguing directly with local players. And only after we have interacted with the community, understood their ideas, we start to propose. We as architects must propose, we must be moderators of design and we must be visualizers. This way we can actually create the glue that can bring people together around our visualizations. By doing this, our visualizations are not mappings: they have the power of politics.

I remember reading a comparison between Torre David and the Domino House: both of them are in fact open systems. So, in a way, this suggested that the role of architecture should be to propose open systems. How will this change the role of the architect in the future? Will architects still design buildings?

Well, fortunately we’re living in the era of the internet, of social media, of all kind of collaboration tools, so we don’t have to sit in the same room to collaborate. The central point is about sharing and creating open source processes, not necessarily buildings. What we have to create is the framework for architecture to happen. We need to merge planning, landscape, architecture all in one. We need to actually work in much more interdisciplinary ways. We need to house 2 billion people coming on this earth in the next 30 years, and most of them (75%) will be in poverty. We have to build fast enough and cheap enough and good enough.

Coming back to Latin America, the case of Latin America is very site-specific. Can it be used in any way to form the design of the future cities in different parts of the world?

Of course it can, because Latin America is pretty much 80% urbanized. China is 50% urbanized. Europe is around 65% urbanized. But Venezuela is 89 urbanized and most of the people are living in the cities. Therefore there is already a great experience with hyperdensity and hypergrowth, with the failures of modernism and also with the cities built by people.

What is already happening in the peripheries? What are the current trends and what will be the future trends?

They are urbanizing at a very high speed. All they need is a little bit of a push to create a few key things like transportation, sewage and so on. With this acupuncture the periphery will urbanize beautifully. All you need to do is change the laws, make incentives for people to build the cities themselves. So, again, what we need is to actually let people build the cities themselves, empower thousands of developers to make buildings themselves.

So peripheries need a push. But what approach should then be followed to further develop these cities that have already been built by people, like South America peripheries? Does it have to be reactive, proactive or retroactive planning? Or a mix of them?

We need retroactive urban planning and we need to demonstrate to the government what is happening to the cities and what these cities and people need. We need a new language to describe the urban phenomena: people and politicians now have understood manhattanization and hyperdensity, but they didn’t understand the real complex issues of periphery and urbanization like ambiguity, hybridization and alternative development schemes. So we need to make the maps to show the situation of cities, do research, more observing that may lead to applied research which will lead eventually to intervention and buildings. But we should not think about constructing a building that has to be done in one year and give profit after one year. We have to think about the city building overtime.

People living in Torre David have been evicted. What is going to happen now?

Actually 50% of the people have been evacuated and there are 50% of the people living inside. The evacuated ones are 67 km away from the tower and from their work, in a very hot desert area of the city. What I think is going to happen is that people will take those houses that were given to them for free, then they will sell them and they will move right back into the cities, probably to a barrio. Therefore, the saga of Torre David is not finished.

WE NEED TO HOUSE 2 BILLION PEOPLE COMING ON THIS EARTH IN THE NEXT 30 YEARS, AND 75% OF THEM WILL BE IN POVERTY. WE HAVE TO BUILD FAST ENOUGH AND CHEAP ENOUGH AND GOOD ENOUGH

I think Torre David could have been one of the most sustainable high-rise projects ever, because people worked in one mile radius around the building, some of the apartments in Torre David were beautiful and finished and they are not slum-like at all: the residents were investing heavily to create good infrastructure in Torre David, with connection to sewage and electricity, it was right in the center of the city and connected to transport infrastructure; people were just building their houses over time.

Torre David was a symbol. When we brought the story of Torre David to Venice, it was an intentional effort to create a spectacle aimed to talk about architecture, a different kind of architecture, alternative to traditional versions of modernism. I think the exhibition was successful because people realized that it was more interesting to think about a process rather than a project.